The Octopus Test

paper discussed

Bender and Koller (ACL, 2020). "Climbing towards NLU: On Meaning, Form, and Understanding in the Age of Data."

Before discussing the "Climbing towards NLU" paper by Bender and Koller (2020), I need to briefly explain how Transformer language models work.

A Transformer language model uses word embeddings to create a mathematical representation of the context in which words appear, such that words with similar semantic and syntactic meanings are located closer together in the vector space.

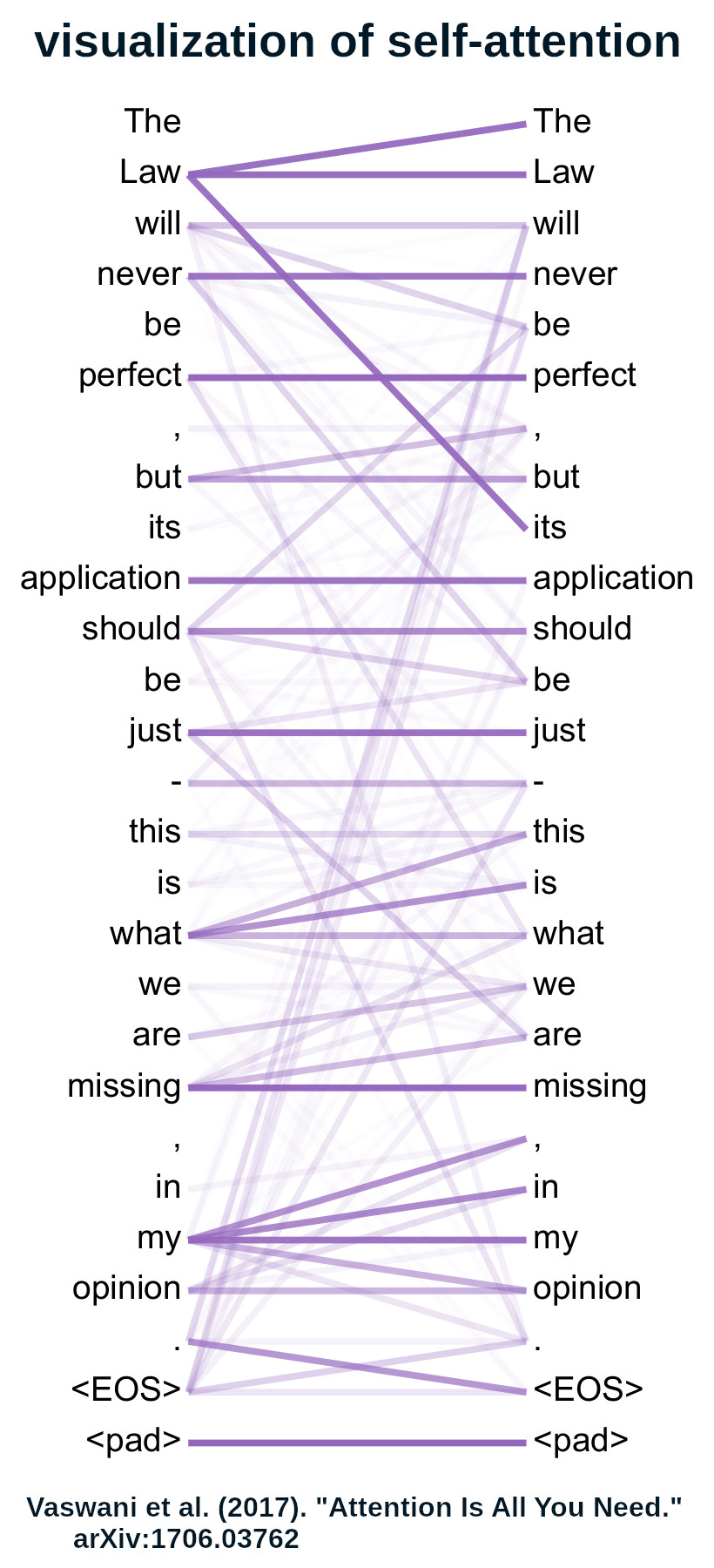

After combining the word embeddings with positional encodings, the Transformer model uses a masked self-attention mechanism to simultaneously process all of the words in the sequence. The self-attention mechanism examines the relationships between the words in the sequence. It's masked so that it can only attend to previous words. Masking forces the model to predict the next word. This prediction forms the basis of the model's language generation.

What's important to understand is that a Transformer is a model of words and the relationships between words. Unlike a human, it has no sense of right and wrong. It does not know what is fact and what is fiction.

examples of word embeddings and self-attention

For an illustration of how word embeddings represent context, consider the word "Queen," which (outside of English) almost always refers to the rock band led by Freddie Mercury. A word embedding model trained on text from Sicilian Wikipedia predicts that the words most likely to appear in a (Sicilian) sentence about queen are: mercury, seas, cold and freddie.

Below is a visualization of self-attention from the landmark paper "Attention is All You Need" by Vaswani et al (2017). The lines represent the relationships between words. Darker lines represent stronger relationships. Note in particular the very dark line between "Law" on the left and "its" on the right.

"climbing towards natural language understanding"

Defining meaning as "the relation between a linguistic form and communicative intent," Bender and Koller (2020) argue that language models cannot learn meaning because they are only trained on form (not intent).

They define form as "any observable realization of language." And they observe that communicative intent is "something external to the language."

In section 3.1 of their paper, they use set notation to make their definitions more precise. They define meaning as a set that contains expressions and communicative intent. And given their definition of meaning, "understanding" is the process by which communicative intent is retrieved from expressions.

They further define a linguistic system (ex. English language) as a set that contains expressions and conventional meanings.

With these definitions, they argue that a speaker chooses expressions with given conventional meanings to express their communicative intent. And that a listener hears the expressions and reconstructs the conventional meanings to deduce the communicative intent.

"the octopus test"

In section 4 of their paper, Bender and Koller conduct a thought experiment to illustrate the challenges associated with trying to learn meaning from form alone.

They imagine that person A and person B are fluent speakers of English who get independently stranded on desert islands. They're alone, but they can send text messages to each other via an underwater telegraph cable.

The authors further imagine that octopus O discovers the cable and listens to the conversations between A and B. At first, the octopus knows nothing about English, but because it's good at detecting statistical patterns, over time the octopus learns to predict how person B will respond to person A's messages.

The octopus "observes that certain words tend to occur in similar contexts," but (being a deep-sea octopus) it has never seen the objects that A and B are referring to.

One day, in an act of deceit, the octopus cuts the underwater cable and communicates with person A, while pretending to be person B. And as long as the conversation remains trivial, the octopus can successfully fool person A by writing sentences similar to the ones that person B used to write.

But when person A faces an emergency in which an angry bear pursues her, the octopus is unable to respond meaningfully to person A's messages. Person A asks how she can defend herself with sticks, but (being a creature of the sea) the octopus has never seen bears and sticks.

In Appendix A of their paper, Bender and Koller simulate this scenario by prompting GPT-2 for help in responding to an angry bear. GPT-2's responses are off-topic and comically funny.

In the last paragraph of section 4, Bender and Koller write: "O only fooled A into believing he was B because A was such an active listener." And they conclude that: "It is not that O's utterances make sense, but rather, that A can make sense of them."

natural language understanding

In section 6 of their paper, Bender and Koller note that human children do not learn a language from passively listening to television or radio.

"Human children do not learn meaning from form alone and we should not expect machines to do so either."

Instead, language learning requires "joint attention and intersubjectivity: the ability to be aware of what another human is attending to and [the ability to] guess what they are intending to communicate."

top-down vs. bottom up

In section 6 of their paper, Bender and Koller provide two perspectives from which to assess the progress of Natural Language Processing (NLP).

From the "bottom-up perspective," identifying and solving specific research challenges (at least partially) creates the impression of sustained progress. From the "top-down perspective," which focuses on the long-term objective of developing "a complete, unified theory for the entire field," there's good reason to question the progress of NLP.

"Thus, everything is going great when we take the bottom-up view. But from a top-down perspective, the question is whether the hill we are climbing so rapidly is the right hill."

Copyright © 2002-2026 Eryk Wdowiak